You can read Part 1 of this essay here:

“Porque morir no duele, lo que duele es el olvido.”

(Because dying doesn’t hurt, what hurts is oblivion.)

— Subcomandante Marcos

“Decolonizing means reinscribing the suppressed, the ruinous, in the present.”

— Javier Sanjinés (2013)

“Let us crouch by the fire in an old way that is forever new.”

— Martin Shaw (2020)

Going back?

As I have written about in other essays, decolonial projects like revitalization or re-existence are not about ‘going back’ or romantically harking back to a fantasy of the ‘good old days’. I can’t speak for anyone else’s context, but in Ireland I think I can say that there were no good old days – at least as far as cultural memory spans. However, there were days when there were no globalised systems rapidly eroding the basis for much of life on Earth as we know it to exist. There were days when there were cultural limitations to such things being able to occur, and I think that’s worth consideration and exploration. This caveat about ‘going back’ is necessary when having discussions about the ‘value’ of the past because of the centrality of the romanticisation/vilification dichotomy within modernity’s narratives, and because fascism typically mobilises some kind of ‘going back’ narrative. Both romanticisation and vilification function to generate separation between us, the ancestral dead, and the land. If we get caught up romanticising or vilifying our ancestors and nature, we are not allowing them the inherent complexity, paradoxes, and messiness that comes with being alive. Both narratives are simplistic, and both are defeatist – in a way it’s a grave we dig for ourselves too. Neither allow us to move towards the messy heart of things and neither are a basis for healthy relating. Romanticisation tends to happen as a reaction to the felt reality of modernity’s reliance on the vilification of the past. Modernity vilifies and erases the past as a way to position itself as the ultimate and only valid historical point of arrival for all humans and the planet.

The idea that we could even consider ‘going back’ carries with it colonial assumptions about ‘time’ and ‘history’, where the ‘past’ is positioned on an imaginary linear timeline as something that is distant, dead, static, and irrelevant to what is taking place in the present-future. As culturally modern people, we’re conditioned to believe the past can’t offer anything of relevance to the contemporary predicaments of modernity, that a yet unrealised promise of a future utopia is the only place things worth knowing, seeking, or doing can be sought. This hubristic outlook is part of what modernity calls ‘progress’. The ‘best’ is somehow yet to come if we just do more of the same things that created the predicaments we’re in. The ‘past’ is only seen to have any value for its utility in creating more of the same. Even at that, on a discursive level modernity only draws from its own internal past since it is a self-referential system that attempts to invalidate everything but itself. In practice, Western modernity has been built on many different forms of theft and appropriation from other cultures and other ‘pasts’.

Sophie Macklin uses the term ‘deep present’ to gesture towards the layers of deep time – personal, ancestral, and cosmic – that are the inherent fabric of what we experience as the ‘present’. The ‘present’ is not merely what we see before us in any fleeting instant, somehow imagined to be unmoored from past and future, but something that has ever-broadening depth, something that contains infinitesimal layers. We and everything around us inherently inhabit and embody this depth. For example, it took billions of years for our bodies to come to take the complex forms that they now take. That time depth is inherent in the present of our individual lives. What might this mean for our connection and responsibilities to our ancestors if they (human and non-human) are ever-present in the layers that shape the foundations of our experience? What if we started considering the land itself as ancestor, and something we are ancestors to and within in a non-linear way? ‘Time’ is not some discrete thing that happens in an abstract vacuum – for us it is movement on the land and in our bodies; it only makes any kind of experiential sense within life’s cycles and constant change.

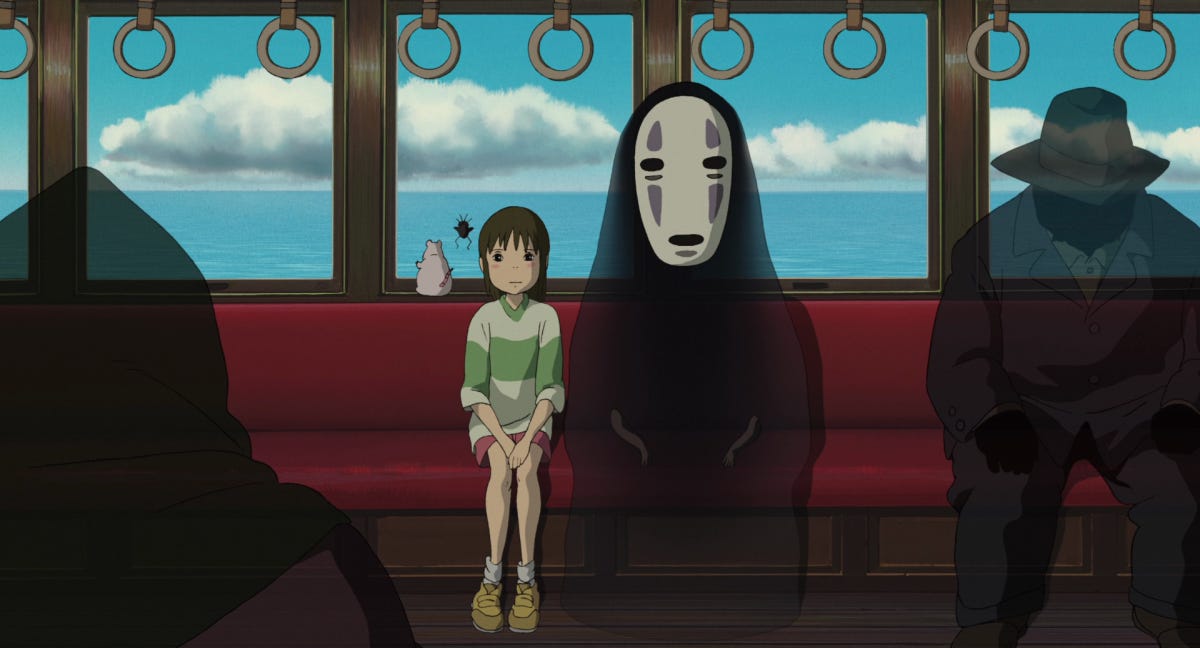

Rather than being something that is ‘finished’ and far away, the past is alive in every moment of the present, and continually influences and shapes future possibilities, even births them. The past is itself altered by how we continue to relate with it or our refusal to do so. Dwayne Donald’s (2020) definition of colonialism as “an extended process of denying relationships” gives us something to consider here. Relationship denial doesn’t make a relationship go away, it means we’re neglecting the responsibilities we hold within that relationship. If we’re in denial about our relationship to the past, in practice we are extracting from it unidirectionally and not examining the responsibilities we hold. This was beautifully portrayed in Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 film Spirited Away, where the main character Chihiro winds up on the ‘Sea Railway’, which now travels only one-way through the sea of the spirit realm because people in the living realm have been neglecting to tend those relationships.

The modern individualist cosmology conditions us to think we should focus solely on ourselves as imagined individuals (or the heteronormative nuclear family) and extract whatever we can from life while we’re alive, without any consideration for the wider responsibilities towards life that inherently come with being alive and inhabiting Earth. In other words, we are conditioned into this cosmology which is predicated on sanctioned denial. There are many different responsibilities to be considered, but one such set of responsibilities is towards the ancestors (human and non-human), as the basis from which our own lives emerge, and the erasure they are facing at the hands of industrial civilisation. The oblivion we create for the ancestors is one we equally create for ourselves in this timespace of amnesia, hubris, scarce wisdom, and unrelenting noise which John Moriarty called the ‘noisesphere’. The Zapatistas use the word olvido (oblivion) to name what the trajectory of the Mexican state and global colonial-capitalist system’s violence has meant for them. With their ‘re-existence project’ they declared una guerra contra el olvido (a war against oblivion) in 1994 (Marcos, 2022). Wiktionary defines olvido as “forgetting, ending of memory.” The example of sentence usage given is, “enterrar en el olvido ― to (try to) forget for ever (literally, ‘to bury in the oblivion’).” The emphasis on trying to forget is critical here. Denial functions most effectively in an environment of amnesia. Fanon (1961) wrote, “by a kind of perverse logic, [colonialism] turns to the past of the oppressed people, and distorts it, disfigures and destroys it.” Forgetting and amnesia oil the cogs that power modernity. People must first be removed from their ancestral contexts in order to be transformed into functioning parts of modernity’s structures, economies, and modes of being. Nobody came willingly.

Excavating our predicaments on these ‘deeper’ levels may indicate to us what needs tending. If we have a good sense of the inner workings of modernity – such as that forgetting is central to its functioning – we can begin to figure out how re-existence projects can be given vitality in the soil of our lives. Re-membering is a radical political project. The word ‘re-member’ comes from the Latin membrum, meaning ‘limb’, thus ‘re-membering’ is the process of putting our bodies back together, of making ourselves whole again. The violence of modernity fragments and dismembers us, and it does this in part by unmooring us from the past and from connection and responsibility towards our ancestors and the land. What is buried or suppressed is not destroyed forever – it shifts and changes form. Maybe there is something to ‘go back’ to after all if it means coming back to ourselves. If we really tried to remember, how could we continue to bear what we currently endure? Gloria Anzaldúa (2015) called this process of re-membering the ‘Coyolxauhqui imperative’ after the Aztec goddess of that name who becomes dismembered in traditional stories. Anzaldúa writes,

“The Coyolxauhqui imperative is to heal and achieve integration. When fragmentations occur you fall apart and feel as though you've been expelled from paradise. Coyolxauhqui is my symbol for the necessary process of dismemberment and fragmentation, of seeing that self or the situations you're embroiled in differently. It is also my symbol for reconstruction and reframing, one that allows for putting the pieces together in a new way. The Coyolxauhqui imperative is an ongoing process of making and unmaking. There is never any resolution, just the process of healing.”

Nation states, standardization, and dismemberment

To re-exist in this context is to find ways to re-member and re-embody modes of being & knowing that honour the “paths into the future that have been severed by coloniality” (Vázquez, 2020) in spite of or as an act of disobedience to the Euro-American monopolization of knowledge, being, meaning-making, and existence that dominates the entire island of Ireland today, north and south.

If political independence for the southern state - the so-called ‘Republic’ - did not herald an end to coloniality, but rather a fervent upscaling of modern/colonial processes and the Eurocentric civilizational paradigm, then there is no reason to suggest that a nation-state based ‘reunification’ of north and south would suddenly mobilise a politics of interruption to it either. There is not much indication of concern about coloniality within the political landscapes across the island, other than in fringe pockets. It is easy to point the finger at the northern state and rightly call it a colonial project. While different in character, it is no more a colonial project than the Irish Free State or Republic, or any nation-state project across the planet for that matter. Social organization based on nation-state structures and modes of reproducing what it means to be human are fundamentally colonial in origin and in continued function. Nationalism and the state functionally attempt to standardize all of life within the territories they claim jurisdiction over. To standardize, you need standards. What are the standards of modernity’s standardizing project, and where did they originate from? Ultimately, the ideal modern standards of what it means to be human were established during the so-called ‘Enlightenment’, a period of intellectual reform by elite white European men which in large part functioned to provide frameworks and justifications for the planetary cataclysms of colonial violence. Which, most significantly, included the development of the concept of race that is the “condition of possibility” (GTDF) for the modern/colonial world-system to exist and persist. As Andrews (2021) notes, “Racial science arose as a discipline to explore the superiority of the White race, and it is telling that basically all the key Enlightenment thinkers were architects of its intellectual framework” and “had the world not been built in the image of White supremacy the racial intellectual framework of the Enlightenment would have been impossible.” These ‘standards’ are part of the enclosure of modern existence, the boundaries of which nation state structures enforce, both Irish states included.

The catch is that life can never be successfully ‘fully’ standardized in practice. Erasure can almost never be a completed project. Colonial violence has not been so total as to erase every last trace of our collective pasts. Instead we get the kinds of chaotic and far-reaching crises we’re living through, ultimately rooted in the disruption of our ancestral futures. A lot of harm and damage is done through the attempts to standardize, homogenize, assimilate, or erase, but humans and other beings exist, and re-exist, regardless and in spite of this continued violence. Standardization can be seen as a process of dismemberment and being reconstructed in a completely imbalanced and lopsided way, where our bodies constantly remind us in various ways how out of kilter we are. Re-existence then is a project of re-membering and reconstructing ourselves in an “old way that is forever new.”

Ruins and re-existence

For a start, bearing witness holds power in the face of oblivion and is an incredibly important task. Bearing witness is a refusal to take part in the active forgetting, the active interment in oblivion. The storm of progress is relentless, and bearing witness is a refusal to dissociate from that. Sometimes it is all that can be done when the collective will is not there for more than that, and even then many times will by itself is not enough to overcome the storm as historical struggles show us. Bearing witness is keeping a small fire lit in remembrance that there was before, still are, and can be other ways to exist than the relentless violence of modernity which tries to convince us that things have always been this way and always will be. Machado de Oliveira writes in Hospicing Modernity (2021) that there is a constant tightrope to be walked between projective hope and projective hopelessness, and that her book is about “rescuing hope from the cages of projections into the future and enabling it to weave relationships and movements in the present—the very texture that futures are made of.”

Benjamin’s (1942) ‘angel of history’, with their wings caught by the force of the storm of progress, saw a “single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage” where “we perceive a chain of events.” These ‘wreckages’ are folded into the many layers that make us. The ‘wreckages’ are already, always us. We aren’t external to them. To return to Sanjinés’ quote at the top of the essay: “decolonizing means reinscribing the suppressed, the ruinous, in the present.” We carry the ruinous inside us just as it is all around us, anterior to us, and posterior to us, it is all a fractal. The fragmented, dismembered, utilitarian landscapes of much of Ireland are not merely a metaphor for what is happening with us on cultural and spiritual levels, it is all part of the same colonial process. The revered Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durruti famously said,

“We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth; there is not the slightest doubt about that. The bourgeoisie might blast and ruin its own world before it leaves the stage of history. We carry a new world here, in our hearts. That world is growing this minute.”

To twist Durruti’s quote and take it a bit out of context, maybe we can accept the ruins as part of who and what we are, even though more are being created by the storm all the time. Maybe we could see the ruins as the ‘historical hope’ (see quote from Vázquez at the top of Part 1 of this essay) we already inherently carry, the deep layers that give us meaning beyond the short-sightedness of modernity’s present. Without these ruins we would be truly lost facing the void of modernity’s ever-growing oblivion. To re-exist then is to find ways of rebuilding with the ruins in the context of our every-day lives and relationships.

References

Benjamin, W. (1942) On the Concept of History. Available at: https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html (Accessed 22 September 2023).

Machado de Oliveira, V. (2021) Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Vázquez, R. (2020) Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary. Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund.

Donald, D. (2020) Homo Economicus and Forgetful Curriculum: Remembering other ways to be a human being. Available at:

Fanon, F. (1961) The Wretched of the Earth. France: François Maspero.

Andrews, K. (2021) The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World. Great Britain: Allen Lane.

Sanjinés, J. (2013) Embers of the Past: Essays in Times of Decolonization. Durham: Duke University Press.

Shaw, M. (2020) Courting the Wild Twin. UK: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Marcos, S. (2022) Zapatista Stories for Dreaming An-Other World. Oakland: Kairos Books.

Anzaldúa, G. (2015) ‘Let Us Be the Healing of the Wound: The Coyolxauhqui Imperative—la sombra y el sueño’, UNAM Voices, Vol. 120, pp. 120–22.