Revolutionary movements need to re-root in tradition and tradition needs to become revolutionary

Relational Traditions Against Modern Civilization (Part 1)

“Civilization has no relatives, only captives … Its survival is expansive unending hunger, a hunger that has been named colonialism; a vast consumption that feeds on spirit, and all life.”

— Klee Benally (2023, p. 316)

“This colonization meant different things, but the most central was that you no longer owned your own body; that the people became the property of the state. Until that moment it was legal to empower yourself by nature, and this became illegal.”

— Jungle Svonni (2025)

“The decolonial task is to understand and face the loss of relational worlds and, with them, the loss of earth. It is about the restitution of hope in the possibility of enacting relational ways of inhabiting earth, of being with human and nonhuman others and of relating to ourselves.”

— Rolando Vázquez (2017)

Note: My numbered footnotes provide additional context, qualifiers, explanations of more technical terms, and (un)necessary side quests. They’re worth reading by themselves as they’re almost like a parallel essay. It’s easy to hover over them on a computer but I’m not sure it’s as easy currently to flick back and forth on the mobile app – sorry about that – hopefully Substack improve the function.

Introduction

The basic premise of this essay series is that tradition1 needs to be revolutionary2, and left-wing revolutionary movement, action, and analysis need to become re-rooted in tradition. The space in between is an emergent, yet ancient, paradigm I am trying to gesture towards — something that Indigenous societies such as those of the Zapatistas, the Mapuche, and others broadly demonstrate the power and necessity of, but that many other societies have completely lost sight of. To be traditional without nationalism. To be revolutionary beyond ideology – because our ancestral communal existences with the Land are unquestionably worth defending or fighting to re-establish.

This paradigm is something that does not yet exist in predominantly white societies where ‘traditionalists’ are mostly either depoliticised or conservative, and leftists are mostly still in tangles over various dead ends: economic and class reductionism, electoral politics and party building, myopic and facile attempts to ‘seize power’ or build ‘dual power’, liberal and technocratic solutionism, and hungering searches for universal answers in the struggles and traditions of other peoples. All while remaining alienated from their own ancestral cultures, relations, ecological knowledges, and the land they’re on.3 What should be the natural and congruent integration of tradition and revolutionary politics seems yet distant in Ireland and other Global North contexts where both the left and ‘traditionalists’ are still largely enclosed by modern industrial civilization and the onto-epistemologies4 undergirding it.

As modern/colonial civilization continues to crumble globally, and biosphere collapse intensifies, many people are also beginning to search for meaning in ancestral traditions and are looking to the past for guidance on alternative ways to live, organise our societies, reconfigure relationships with the Land, and re-exist as Earth-beings. I think these pathways are necessary, but they are laden with dangers and traps that can easily redirect us into reproducing modern ways of knowing-being-relating, leaving the Leviathan5 that has created this mess and is destroying us entirely untouched and unchallenged, or even giving it new leases of life.

We cede tradition to conservatism, fascism, and ethnonationalisms at the peril of ourselves and planetary life. Tradition calls for antagonism with the state, capital, and reactionary groups.

This is the first part of a multi-part essay series exploring these ideas, relationships, possibilities, paradoxes, and tensions.

Traditionally, we all belong to Land-centred communal existences that include all other beings, forces, and spirits of the Land. In their unquantifiable pluriversal forms, expressions, and weaves since time immemorial: there are no ancestral traditions older and more relationally durable than those that honour, foster, and defend this belonging. In this essay series I refer to such traditions or those that broadly move in the direction of this belonging as ‘relational traditions’, which I loosely contrast with ‘anti-relational traditions’.6

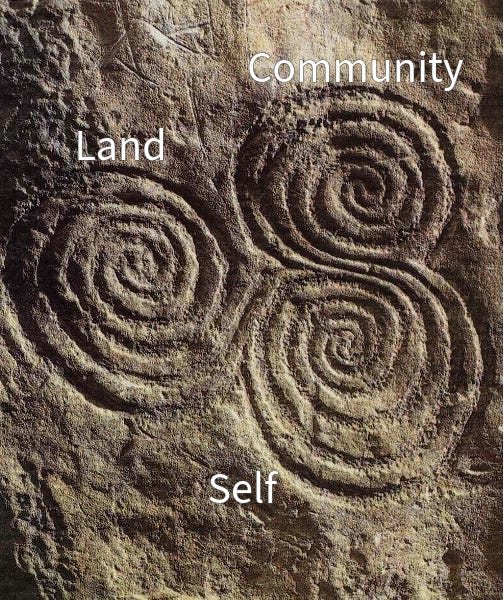

Taking inspiration from my own ancestral cosmologies, I imagine this belonging constituted by a triad of integrated relationships between Land, Community, and Self7 — depicted below as the ‘spiral motif’ found in Síd in Broga (Newgrange). I attempted to translate this triad into Gaeilge, but I found that the words I wanted to use already encompassed relational integration, so I chose to leave it in English which accurately and honestly reflects our cultural disintegration.8 The fact that we can even imagine not belonging, or that we take for granted living in such severe cultural disintegration and alienation from each other, the Land, and our own selves, is a reflection of the dominance and naturalisation of modern civilization’s anti-relational traditions over our cultural understandings and constructions of reality.

What is relationality?

“At its heart, relationality points to the radical interdependence of all things.”

… “Adding to the challenge is that relationality is not fully comprehensible as a concept. And even if it were, how would we even describe it using the languages and concepts from the old story [of modernity]?”

— Escobar, Osterweil, and Sharma (2024)

In other words, how can we describe relationality from within the anti-relational traditions of colonial modernity — of which this globally hegemonic colonial language in which I write is structured by, and in turn itself structures? We can’t really. But paradoxes can bear fruit if we’re curious enough.

These are some culturally specific expressions of relationality:

Vincularidad is used by the Andean Indigenous thinkers Nina Pacari, Fernando Huanacuni Mamani, and Félix Patzi Paco:

“Vincularidad is the awareness of the integral relation and interdependence amongst all living organisms (in which humans are only a part) with territory or land and the cosmos. It is a relation and interdependence in search of balance and harmony of life in the planet.” (Mignolo and Walsh, 2018, p. 1)

In Māori cosmology,

(2025) writes:“For us Māori to say “Kō au te awa kō te awa kō au” which means: “I am the river and the river is me” is not a metaphor, it is a material statement of fact. You are the river in the same way a wave as the ocean, an emergent expression of a larger continuous body of matter.”

In my own ancestral Gaelic cosmology, Meighan (2022) suggests Dùthchas (written in Scottish Gaelic, or Dúchas written in Irish Gaelic):

“Dùthchas, as a Gaelic ontology and methodology, stresses the interconnectedness of people, land, culture, and an ecological balance among all entities, human and more than human.”

For the Anishinaabe, aki “includes all aspects of creation: land forms, elements, plants, animals, spirits, sounds, thoughts, feelings, energies and all of the emergent systems, ecologies, and networks that connect these elements” (Simpson, 2014). While mino bimaadiziwin “means living life in a way that promotes rebirth, renewal, reciprocity and respect” (Simpson, 2011, p. 27).

For the Mapuche, Elisa Loncón (2023) writes:

“...Azmapu, the philosophy of good life, which speaks of caring for the “lof” or community and protecting people and nature, this has contributed to maintaining the condition of Aboriginal nation, knowledge, values and language. The Mapuche philosophy seeks the good life, maintaining the indissoluble link between people and nature, it recognizes the earth as mother, respects the life of all beings such as the mountains, rivers, hills and birds. We also understand that human beings find ourselves in this world to take care of each other and to take care of the earth.”

These different understandings and expressions of relationality, and life lived in accordance with a relational cosmology, are not conceptual or ideological. They are not rules, prescriptions, dogmas, goals, theories, agendas, programmes, platforms, documents, treaties, agreements, manifestos, or declarations. They aren’t manipulations of numerical data sets. For their actualisation to be materialised in the world, they cannot be separated from how we practice love for each other, the Land, and our own selves as different but radically interconnected manifestations of life. These understandings emerged from ancient societal relationships with life, which became enshrined in cultural traditions. They emerged from relational worlds that were, in their very existence, innately antagonistic to modernity/coloniality, which has repeatedly attempted to destroy relational worlds and parasitically consume their life force. Love is only legible to modernity for what it can produce.

However, Escobar et. al. (2024, p. 7-8) warn that:

“Being related does not by itself entail being responsible, careful, or kind, as is evidenced by many of our family relations, and by the coercive relations through which we are bound to employers, property, and the market … An ethic of true mutuality can never take root in such shallow soil, where the words ‘relations’ and ‘relationship’ mean the management of transactions between capitalists, workers, and consumers, or the creation of ‘value chains.’”

As such, anti-relational traditions and ‘non-relationality’9 are not so much characterised by the absence of relationships as they are the denial of them. Dwayne Donald (2020) gives a definition of colonialism as an “extended process of denying relationships”. Patriarchal relations deny the existence or importance of various kinds of work and energy that women and queer people are relied upon to put into the most intimate forms of social reproduction. On the part of the enslaver, slavery requires systemic denial of the personhood and humanity of the enslaved person, which is central to the maintenance of the relationship in that configuration. What makes one a settler in a settler colonial society is the material validation of one’s cultural existence within the structures of that society which are supported by the denial of the historic and ongoing genocidal and ecocidal relationships that undergird the entire existence of that society. For modernised people to imagine ourselves as ‘individuals’ requires a denial of the constellation of colonially constituted relationships with the Land and other peoples around the world whose subjugation and exploitation support the fantasy of our imagined self-sufficiency. At their root, all of these things are upheld by cultural traditions in one form or another.

Relational traditions vs. modern civilization

Tradition, of all kinds, carries incredible potency and power, and it is territory that the left (broadly) has actively cast away and ceded to political opponents who understand its power, and who use it to maintain hierarchical systems of domination. Equally, custodianship of traditional culture has become bereft of revolutionary and insurgent analyses and ethics. The essence of what made many traditional cultures threatening to states and colonizing forces initially now seems all but abandoned with depoliticised and decontextualised traditions and traditional forms being commodified for romanticised tourist or ‘self-help’ consumption, and otherwise assimilated as window dressing into the normativity of the house of modernity. Many ancestral traditions would have been born in socially and culturally antagonistic worlds to modernity — which Simpson (2011, p. 18) describes as “the dynamic, fluid, compassionate, respectful context within which they were originally generated.”

The ultimate power of ancestral traditions is in their potential to provide a cultural basis10 for us to steward, nurture, and defend deep relationships of care and reciprocity with each other and with our specific places across our dear, suffering planet. Left-wing movements historically have relied on ideology and political structure alone, and have rarely ever imagined beyond or dared to attempt to step beyond the onto-epistemological (see footnote 4) enclosures of modernity/coloniality, which traditional ways of knowing-being-relating can provide us with a precedent for doing. Relational and land-centred traditions are the proven “success” of many contemporary societies, and of all of our most ancient ancestors, human and beyond-human, over millions of years – which is not to say they were without problems, ‘perfect’, ‘utopian’, ‘pure’, ‘conflict free’, ‘innately good’ etc. “Utopia is a colonial logic” (Benally, 2023, p. 361).

If we truly want to create “sustainable”11 or ecologically attuned societies, we need to dig much deeper and begin with traditional cosmologies, practices, knowledges, and lifeways that safeguarded relational worlds for long aeons before any human societies started becoming “unsustainable”, ie. before they started tending towards inevitable collapse due to cultural traditions that function to entrench coercive hierarchies and ecological domination. This doesn’t mean uncritically trying to recreate relational traditions either. Social context and specificity is important. We are now, we are not then.

Civilization12, by contrast with how many other societies have structured themselves throughout deep time, in its current planetary form spearheaded by the modern/colonial nation-state, armed with its hubristic mythologies of ‘progress’, inevitability, necessity, saviourism, and superiority, has unnecessarily brought untold suffering and unprecedented deterioration to all planetary life in a short period of time: mere centuries and millennia.

Alienation, amnesia, confusion, fear, and disintegration are civilization’s cultural grammar of erasure – all in the name of its own anti-relational traditions of violence, coercion, control, exploitation, extraction, and the hierarchical consolidation of power.13 As such, modern civilization cannot tolerate relational traditions that foster any combination of autonomy, communal togetherness, collective responsibility, interconnectivity, genuine creativity and imagination, care, mutual aid, generosity, reciprocity, an-archy (without rulers), and relational attunement. Violence that seeks to erase such tradition seeks to erase our spirit and undo the delicate relational fabric that holds all Earthly life together. We’re now at an acute stage of that undoing (Ceballos et. al., 2017).

It is as a result of thousands of years of our disinheritance of lives lived in intimacy with the Land, a process intensified and accelerated by modern colonialism, that we can even consider the possibility of not belonging to the Earth – that such relational traditions are now not the default waters we swim within by virtue of being born human. Civilization’s violence is a nightmarish disruption to the ancient, harmonious dis-order of the Land. If we choose not to revitalise relational traditions that bring us closer to each other and the Land in new ways informed by the old, and intentionally overturn anti-relational traditions, whatever that looks like in our specific, cultural, place-based contexts, Earth may lose us altogether to civilization’s out of control, all-consuming death-drive.

Relational and anti-relational traditions

‘Tradition’ is contested, heterogeneous, nebulous, and context-specific. It is not any one definable or confinable ‘thing’. In some ways, it’s everything we do (and don’t do). It does not exist outside or independently of the lived realities of actual people – something modern people can forget when digging for ancestral traditions.14 It’s not an object to be consumed.

This differentiation between ‘relational’ and ‘anti-relational’ traditions is not an attempt to create a clear-cut categorical binary, nor a universally applicable one-size-fits-all theory, but as a way of centering the question of relationality when sorting through the complex and sometimes paradoxical and contradictory terrain of tradition — particularly in European contexts that have a lot of shit to sort through and compost in recent ancestral memory. In general, we can ask ourselves, “what does this tradition foster?”, “where can things go wrong”, or “where can things go right?” Does the tradition in question move “toward greater suffering or its alleviation”? (Escobar et. al., 2024, p. 8)

Traditions transform and change over time, shedding old forms, carrying some others along, and shifting into new ones. When harmful social conditions proliferate and are upheld by a society, the cultural practices driving them can inevitably become ‘tradition’, such as patriarchal family structures. Traditions of all kinds emerge from diverse and divergent human capacities, which can culturally enshrine our capacities for care or for violence depending on social conditions and how we decide to cultivate these capacities. All societies, civilizational or stateless, can and do harbour both relational and anti-relational traditions15 simultaneously, because no society is ever monolithic and hierarchical societies are always in perpetual conflict.16

For example, in Gaelic society for centuries the ‘cumal’, or enslaved women, were the lowest legal social rank and could be held captive for forced domestic labour (Kelly, 1988, p. 95-96). At the same time, hospitality was seen to be and legally upheld as one of the most important traditional pillars of society (Kelly, 1988, p. 139-140). People were expected to share generously with others, and there were hundreds of large bruidne (loosely translated as ‘hostels’) across Ireland sponsored by local chieftains which were obligated to provide food and a bed to anyone freely and without question (Joyce, 1906). Being inhospitable and reneging on responsibilities could spell the demise of kings and chieftains, which the mythological king Bres serves as an example of in the saga of Cath Mag Tuired (the Second Battle of Mag Tuired). It is speculated that ‘bog bodies’ found in Ireland – the ancient remains of people preserved in bogs – may have been chieftains who were ritually sacrificed when they could not provide for people (or perhaps would not – why is revolution not a consideration here?). All of these traditions, slavery, hospitality and social consequences for trying to enforce scarcity — anti-relational and relational — existed in tension and contradiction alongside each other.17

The conservative capture of tradition

“Few concepts have been distorted, both deliberately and unintentionally, in as many ways as tradition has. It is sometimes seen as inert, stagnant, belonging to a dead past; at other times it is taken to be a dynamic means of understanding history.”

— Javier Sanjinés (2013)

In European and European settler contexts to varying degrees the realm of tradition has generally been so severely ceded by the left to reactionary conservatisms to the point that they are almost synonymous politically. The Oxford Dictionary definitions of ‘conservatism’ are as follows:

“commitment to traditional values and ideas with opposition to change or innovation.”

“the holding of political views that favour free enterprise, private ownership, and socially traditional ideas.”

Similarly, in Umberto Eco’s (1995) widely read essay on fascism, Ur-Fascism, he argues that the “cult of tradition” is the first common defining feature between various manifestations of fascism. From Oxford to Eco, this association should be of deadly serious concern to those working to reclaim ancestral traditions in almost any context, but particularly so in predominantly white societies.

Fascists seek to create social orders where anti-relational traditions proliferate and are upheld by strict coercive and punitive state enforced systems. Since popular and revolutionary movements have shifted some aspects of modern society away from anti-relationality over the past few decades in many Global North societies, fascists and their supporters18 are often, in part, reacting to concessions made by states to these movements. Fascists cast relational traditions which are extant within modernity, or which have been maintained or developed in spite of and in resistance to modernity, or which have been assimilated for counterinsurgent ends into modernity, to be characteristic of the alleged ‘loss of Western values’. This is partially what they mean when they berate ‘modernity’. On the other hand, the decolonial critique of modernity is one that broadly speaks from relational worlds and traditions itself, and even questions the basis and worth of such ‘Western values’ when those values depend on and deny the structural violences of coloniality past and present. Of course, even decolonial discourse itself has been getting used to justify ethnonationalism, as with Hindutva fascism in India, where ‘tradition’ is positioned against the ‘cultural imperialism’ of Western modernity. When in fact Hindutva fascists are entirely of modernity, reproducing modern/colonial civilization, and call upon ‘tradition’ to serve as a naturalising narrative basis for their ethnonationalist authoritarianism.

It is a peculiar situation when you think about it that ‘tradition’ in the most general sense would become synonymously associated with one insidious realm of political ideologies. Why is that? Tradition is so broad, and often so life-giving. This situation is a story of surrender, consolidation of power, modernization, and alienation. It’s a story of traditional cultural belonging becoming subsumed by nationalist ideology – something only achievable once a people have been intergenerationally and culturally alienated from their traditional communal social structures and ecological integration. For some peoples this has taken place quite recently and in the space of just a few generations, for others it’s a centuries or millennia old story. For example, the traditional cultural belonging encapsulated broadly by ‘Gael’ over centuries became the nationality of ‘Irish’, something more closely resembling English culture than Gaelic. This happened through the processes of modernization, colonization, and alienation from Land and tradition – a dynamic repeated across the world to the widespread success of nation-state control over our lives, bodies, and autonomy.

The most fundamental issue here comes with the left willfully ceding the political terrain of ‘tradition’ in its entirety and enabling it to be co-opted and associated synonymously with conservatism, fascism, and ethnonationalisms. We tend to associate ‘tradition’ with the ‘past’, where the ‘past’ is assumed to be nothing but misery and degradation: therefore anything that survives from the past can’t be worth serious consideration for how to live now. This itself is more an effect of societal trauma and amnesia, and all tradition being seen as broadly anti-relational, but tradition itself is not innately good or bad.19 Neither are relational and anti-relational bywords for good and bad: they are to do with human capacities, the ethics and dynamics of relationships, and how these things become enshrined in cultural traditions. The differentiation isn’t a question of purity. Do the traditions broadly tend to foster relational attunement, care ethics, and autonomy, or do they broadly tend to foster violence, domination, and coercive hierarchies?

Crucially, if custodianship of traditional culture doesn’t actively eschew and become antagonistic to the anti-relational traditions of reactionary ideologies, it risks sinking into this already well-beaten pathway of co-optation, capture, and assimilation. Right-wing movements have a long tradition of utilising and weaponising tradition to anti-relational political ends.

The conflation of tradition with reactionary ideologies is itself counter-revolutionary, and ultimately the result of extended and extensive processes of cultural alienation and modernization/colonization. We don’t even realise what we’ve been handing away – we do it so readily. The conflation of tradition with reactionary ideologies holds us back from exploring the true and full possibilities of re-rooting in tradition as the basis for new forms of revolutionary action and change towards the re-creation of communal, Land-centred, and ecologically attuned cultural paradigms that preclude hierarchical and coercive human capacities and ways of relating from being propagated in the ways they have variously been since the end of the last ice age and the beginning of disastrous Holocene20 human experiments with social and ecological control.

If you found this essay helpful or thought-provoking, please share and re-stack.

Subscribe if you’d like to receive the upcoming essays in this series and all my future writing. My posts remain free and I hugely appreciate any paid subscriptions sent my way to support my writing, theorising, and ongoing research. I do not have institutional funding of any kind so each sub goes a very long way.

Check out my Decolonization in Ireland online course

More notes:

I) My attempt here is to gesture at a very broad disconnection that I’ve noticed between revolutionary movements and traditional culture – for all that those two things are coherent ‘things’. While I am advocating for mending this disconnection, I try to avoid any detailed or hyper-specific prescriptions of action beyond that because it is all heavily context dependent, and I’m just one person trying to figure some vastly complicated things out.

II) I’ve tried to avoid essentialism, romanticism, and cultural appropriation in this essay series. This is a hard thing to achieve given the vastness of what I am speaking to here, so I post this knowing there is a risk of getting many things wrong. I am not an ‘expert’ and am constantly learning. I apologise in advance for mistakes that may even come to seem obvious to me in hindsight. I am open to dialogue and correction, and I’ve probably bitten off more than I can chew but these are important conversations.21

Thanks to my partner for the animal drawings and conversations.

Thanks to

for comments and conversations.References:

Benally, Klee (2023) No Spiritual Surrender: Indigenous Anarchy in Defense of the Sacred. Detritus Books.

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., and Dirzo, R. (2017) “Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines” PNAS, vol. 114, no. 30. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704949114

Donald, Dwayne (2020) Homo Economicus and Forgetful Curriculum: Remembering other ways to be a human being

Eco, Umberto (1995) Ur-Fascism

Joyce, P. W. (1906) A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. London: Longmans, Green & co.

(2025) How Indigenous Legends Are Less Superstitious And Less Mythological Than Most RealiseKelly, Fergus (1988) A Guide to Early Irish Law v.3. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Loncón, Elisa (2023) The Mapuche Struggle for the Recognition of its Nation: From a Feminine and Decolonizing Point of View

Meighan, Paul J. (2022) – “Dùthchas, a Scottish Gaelic Methodology to Guide Self-Decolonization and Conceptualize a Kincentric and Relational Approach to Community-Led Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 21, pp. 1-14. doi:10.1177/16094069221142451.

Mignolo, W. and Walsh, C. (2018) On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake (2014) “Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 1–25.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake (2011) Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence. Winnipeg: ARP.

Sanjinés, Javier (2013) Embers of the Past: Essays in Times of Decolonization. Durham: Duke University Press.

Svonni, Jungle (2025) Sámi Shamanism & Spirituality: Interview with Jungle Svonni by

Vázquez, Rolando (2017) “Precedence, Earth and the Anthropocene: Decolonizing Design.” Design Philosophy Papers, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 77–91, doi:10.1080/14487136.2017.1303130.

I am speaking from my own context in Ireland, and mostly to those within Global North, European, European diasporic, and European settler contexts here. If others in other contexts find what I’m saying applicable or helpful, that’s great too (and please let me know if so!)

Revolution from below; horizontal; multiplicitous; pluriversal. A world in which many worlds fit (Zapatistas). I’m not advocating for a top-down revolution (eg. the eventual outcomes of Irish, French, or Russian revolutions). Given ample historical examples of failure and betrayal, I’m skeptical about groups who advocate for a vanguardist, top-down, technocratic (“scientific”; “rational”), vertical revolution or co-optations of otherwise horizontal revolutions. They have historically shown they are not interested in things like equality, autonomy, solidarity, or fairness.

This comes with a big caveat for settlers in settler colonial societies. Relationships with the lands you’re on are not straightforward, and that is beyond the scope of this essay. Ultimately your ancestral task is the disruption of and eventual total destruction of the settler state where you are.

‘Onto-epistemology’ is a compound of ‘ontology’ and ‘epistemology’. Ontology has to do with being, ways of being, existence, and our experience/construction of reality. Epistemology has to do with knowledge, systems of knowledge, ways of knowing, what can be considered ‘knowable’, ways of producing knowledge including what gets considered as ‘knowledge’ or worthy of ‘knowing’ at all. Putting them together speaks to the irreducible intertwinement of ‘being’ and ‘knowing’. ‘Being’ and ‘knowing’ as categories only become discretely and culturally legible through reductive modern/colonial ways of conceiving the world.

This is in reference to Fredy Perlman’s 1983 book Against His-story, Against Leviathan! where he takes up Hobbes’ metaphor of the ‘Leviathan’ for the state and uses it instead to critique the state and civilization. Leviathan consumes and reconfigures everything it comes in contact with, which in turn become part of its apparatuses of domination and control.

While in the process of writing, researching, and coming up with these terms, I came across Escobar, Osterweil, and Sharma’s book Relationality: An Emergent Politics of Life Beyond the Human (2024, p. 4) which suggests almost exactly the same terms of ‘non-relationality’ or ‘anti-relationality’. I am thankful to have come across the book, because a) it’s affirming to see that my thought process aligned through the ether with other writers doing related thinking and b) it gave me an entire book’s worth of thinking from which to enrich this essay series with and dialogue my ideas with.

This framework can easily be read in a modern individualistic way. The ‘Self’ in this is not the modern individuated self that we’ve been socialised to imagine ourselves to be. The ‘Land’ in this is not the object of one-way extractive relationships we moderns see it to be: whether a trove of resources or a romanticised plane for the projection of our ideals. The ‘Community’ in this is not the faint whisper of community we call our social groups and networks in modern society. Decolonization beckons us beyond the onto-epistemic enclosures of modernity, and back to integrated relational belonging.

In attempting to translate this triad into Gaeilge, I found myself wanting to use the word túath for ‘community’. This immediately tripped up the whole process. Túath refers to an older, territorially integrated, emplaced, and culturally specific structure of communal life — it is as much the Land as the people (and unfortunately also the chieftain). ‘Community’ is an impoverished, and maybe even inappropriate, translation for what túath encapsulated. Its occasional colloquial use nowadays seems at odds with this depth and specificity. But if túath already encapsulates both land/territory and community/tribe, then why even have ‘land’ and ‘community’ as separate parts of the triad? Why have the triad at all? The purpose of the triad is to gesture towards a process of re-integration, not try to back-engineer the separability that is structural to modern English onto both modern and old Gaelic words that do not separate existence into discrete ideas — ie. these words already show us a ‘beyond’ to modernity’s enclosures of being-knowing-relating.

Escobar et. al. (2024) write: “one can describe the dominant story as the making of non-, or anti-, relationality, given that it banishes profoundly relational life-worlds and knowledges to the margins or death, while simultaneously enshrining an ontologically dualist worldview in which either/or, subject/object, good/bad, spirit/matter, body/mind, and so on, not only dominate but seem natural.”

I put the word “sustainable” in scare quotes because it is an overused and at this point redundant term, but a lot of people still want something from it. It has been successfully co-opted by counterinsurgent discourses that lure us into thinking more consumerism, the scaling up of industrial technologies, seemingly novel economic models (eg. Doughnut economics, Wellbeing economy), SDGs etc. somehow constitute “sustainability”. The only thing these things are sustaining is modernity.

I don’t use ‘civilization’ as a byword for ‘society’, ie. not all societies are civilizations. While it is something that eludes easy definition, civilizations are hierarchical state-based societies that are usually marked by patriarchy, sedentary agriculture, social class systems, some degree of cultural disconnection from the Land, domestication, and unequal wealth or resource accumulation in some form.

The histories of civilizations are histories of violence, war, and conflict – civilization itself is a war against life. There is effectively no archaeological evidence for organised violent conflict before the emergence of states and civilizations: https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/origins-violence. This doesn’t mean there was never any violence or violent conflict of any kind anywhere ever, but perhaps never anything resembling war, coercive control, or punishment as we know and understand it. Civilizational histories by contrast are evidently littered with organised and systematised violence, which stands to reason because they are always structured by the pursuit of control by smaller groups over larger groups. Such control requires violence to establish and maintain, and it will always inevitably meet resistance. It doesn’t at all mean people in stateless societies are essentially any different to people in societies with states. It doesn’t mean anyone is innately violent or innately peaceful. It just means that there are cultural ways of either enabling or disabling the proliferation of particular ways of relating. We just happen to live in societies that proliferates, normalises, and invisibilises violence.

Worth bearing in mind that modernity itself is also a cultural paradigm.

Stateless societies can harbour both relational and anti-relational traditions, because they are also not monolithic. States and civilizations have to emerge from somewhere. They need to get their beginnings from anti-relationality getting a foothold somehow. It is the responsibility of any people that wish to foster social/ecological autonomy to create and renew traditions that discourage anti-relational capacities and action. Otherwise, who knows, maybe some people could eventually fuck around enough to create a planetary civilization that rapidly annihilates planetary life over a few centuries? Nah, sounds far fetched.. how could that ever happen?

Hierarchical, state-dominated societies are in permanently unresolved states of conflict because people will always struggle for more freedoms or outright revolution against the established order, and the state will constantly try to suppress, contain, or assimilate these efforts.

The fact that both types of tradition always exist alongside each other in hierarchical societies is not a justification for the existence of the state, ie. some kind of perverse liberal or social democratic logic of “things are always bad by default, so we’ll just make them a little bit less bad.”

As an aside: it would be convenient if we could just write the people that comprise reactionary movements off as completely and irredeemably evil – as if they are essentially different and other to us self-appointed “good” people. There are certainly some very nasty people and increasing amounts of ‘regular’ people are being drawn towards them in various ways and for various reasons, all of which need to be understood beyond simplistic good/evil narratives in order to be successfully countered and defeated. We shouldn’t be waiting until all-out bloody conflict is forced on us.

We moderns are obsessed with good/bad, good/evil binaries. It’s a way we try to control reality by fitting it into simplistic fixed categories. It’s another way to circumvent and deny relationships.

The Holocene is the present geological epoch which began about 11,700 years ago as the last ice age of the Pleistocene came to an end with planetary warming. All known civilizations have existed since the beginning of the Holocene, a relatively very recent period in human existence. Some people call it the ‘Anthropocene’, but I don’t like this term for how it is situated within Western progress narratives and tries to spread the blame for the current catastrophe to all humans, or ‘humanity’ as an abstract concept, when many other human societies did not ask to be ripped from their relationship with the Earth by the civilizing forces of colonial modernity.

The inspiration for this note itself is from Escobar et. al. (2024, p. 14) who write, “We want to acknowledge, however, that the work of making relationality visible and comprehensible may run into the dangerous territory of essentialism, romanticism, and cultural appropriation. We understand this and that real harm has been and continues to be caused by doing so. We believe that if relational worldviews are sought after without a material ethic of relationality—one in which accountability, respect, and placedness are considered vital—or with unexamined ideas of the atomized individual without recognizing the relationships and the annihilations that went into making it even possible to imagine oneself as self-sufficient—then there is not only trouble, but we run the risk of falling into the colonizing projects we have been trying to interrupt. Rather than avoid this conversation, we consider it a practice of relationality to address the risks head on, with accountability, compassion, humility, a willingness to make mistakes, be corrected, and learn as we go.”

Haven’t read this in full but THANK YOU! Rooting into tradition, not for the purpose of establishing some discrete racial identity (*cough cough* white nationalism) but re-establishing age-old models of collectivism and expansive kinship

This was thorough. An entire encyclopedia in here! A very generous offering. Thank you. I will need to read through several more times and take notes.