Ireland is not green

This St. Patrick's day, let's map the realities of ecocide on the 'Emerald Isle'

This post contains many images and as a result may be too long to view fully in email. To view all the content, open it on Substack’s website or app.

Most of the images in this post are screenshots from Google Maps satellite imagery, looking over different places in Ireland.

In previous years, Google have posted screenshots of satellite imagery over Ireland on St. Patrick’s day with captions saying that it’s easy to see how it gets called the ‘Emerald Isle’, because a zoomed out satellite view of the entire island looks green for the most part:

For context, the ‘Emerald Isle’ is a term apparently coined in William Drennan’s 1795 poem ‘When Erin First Rose’, but has since entered common parlance. It commonly gets deployed as propaganda to sell a commodified imaginary of Ireland as ‘green’ and even ‘wild’ (as with the official tourism designation of the west coast as the ‘Wild Atlantic Way’). This greenwashed imaginary obfuscates Ireland’s violent histories and continuing processes of ecocide that both the Republic and Northern states preside over and administer. Ireland’s ‘green’ image is routinely used by ‘agribusiness’ corporations to promote their industrial extraction from the land and exploitation of non-human animals.

The historical imaginary of Ireland as ‘green’ precedes the word’s present usage as a byword for ‘environmentally friendly’ or perhaps ‘ecologically intact’ — of which modern Ireland is neither. Nonetheless, the status quo of ecocidal relations with nature in Ireland has benefited from the colour ‘green’ becoming synonymous with these meanings.

What stories can be told by zooming in more closely on specific places? What makes the green places green? What is happening in the places that aren’t green? What stories of ecocide can be seen from the sky?

Grass fields

For a start, what makes Ireland appear so green? For the most part, it’s grass fields and the hedgerows that act as borders between them, visible here:

Grass fields as they exist across Ireland today are not an ecologically neutral or natural landscape. They are industrialised landscapes just as much as the ‘grey unyielding concrete’ of more urbanised places. They exist solely for the purpose of livestock grazing for industrial agriculture. The grass field is constituted by relationships of extraction and domination. If the land were allowed by human society to exist autonomously, these fields would soon get filled in with a diversity of other plants and would, in a short time, reforest itself — enabling all kinds of life to return. Grass fields take consistent maintenance and enforcement to remain as such — nothing else can be allowed to grow or establish itself. Life has no autonomy or dignity in the grass field. The hedgerows that sometimes exist as borders between enclosed fields are often heralded for their importance for ‘wildlife’. They are important, but only because they are the last vestiges of the old forests. Hedgerows are where the small and ‘unintrusive’ forest beings have been allowed to live marginal existences. Other larger forest beings are now gone.

The sprinkling of isolated houses in the above satellite image is a typical scene in modern rural Ireland. In the past it was not like this however: people lived closer together. Agricultural and more ‘wild’ land surrounded the village centres they travelled out from for their subsistence lifeways. And this is only part of the story. Given the static character of satellite imagery, how could it possibly capture movement? Nomadic lifeways were a normal part of society in Gaelic Ireland. The lifeways of Travellers and others that lived nomadically, semi-nomadically, or moved between settlements seasonally would be and are invisibilised by satellite images.

Below is a depiction of what the medieval field system looked like compared to today’s enclosed field system, from Duffy’s Exploring the history and heritage of Irish landscapes (2007). It’s speculated that this general structure could go back as far as the ‘Bronze Age’ in Ireland. While it could be debated whether this pre-modern field system constituted something resembling ‘ecological intactness’, it would certainly be difficult to overstate how much healthier this ecological-relational environment was for humans and the rest of life on the land.

If it isn’t grass fields for industrial agriculture, it’s commercial monocrop trees in tightly packed rows contributing to Ireland’s green hue:

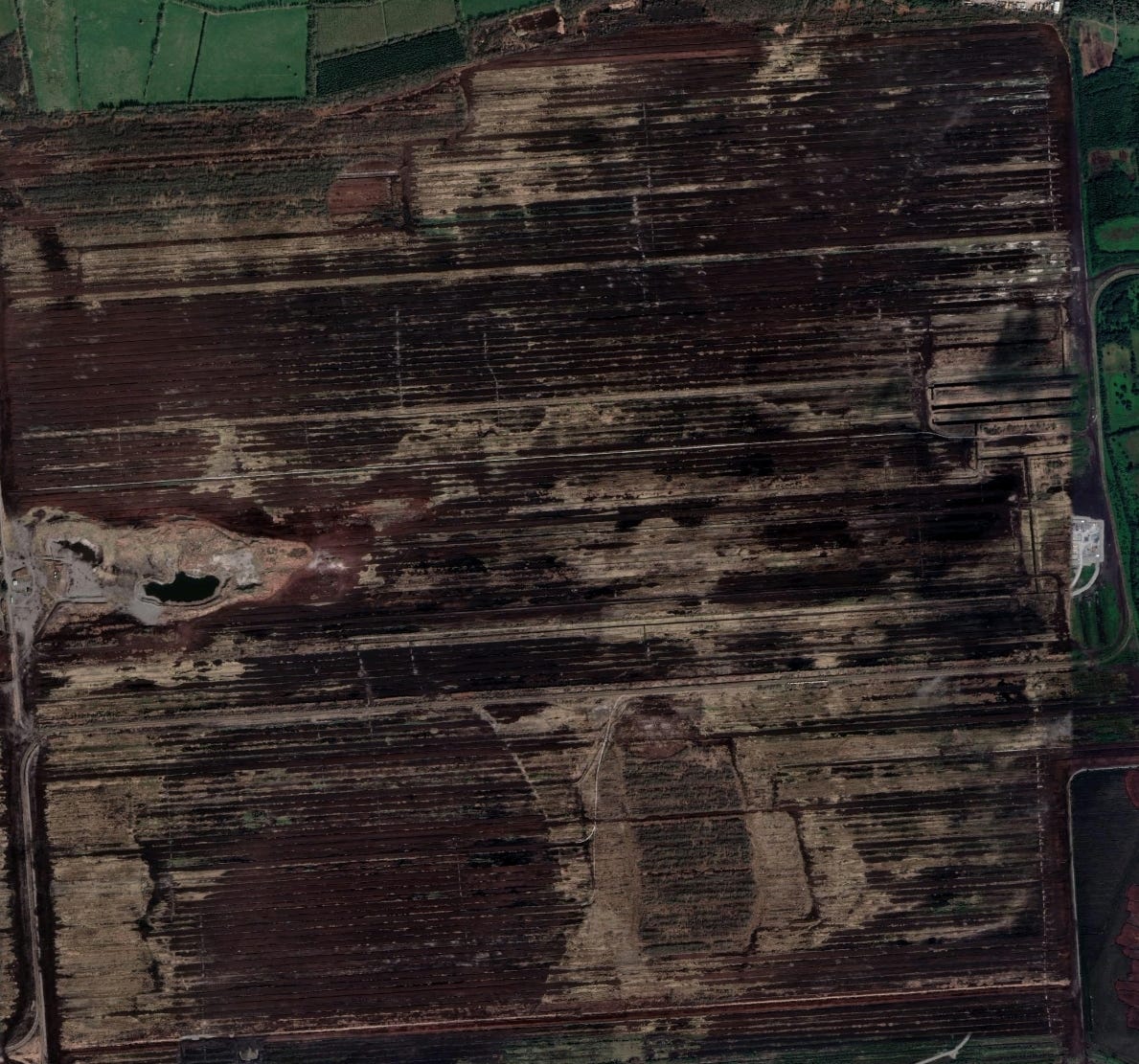

What about these brown patches across the middle of the island?

These ‘brown patches’ tell a story of the ecocide necessary for modernisation. These are Ireland’s bogs. The majority of bogs were heavily depleted for peat which was burned to produce electricity, a practice which ended recently at the end of 2023. About 20% of peatlands remain intact as a result of this devastation. Of course, when Global North countries phase out domestic production of things like peat, the destruction and violence necessary to meet their ever-expanding power consumption are merely outsourced to someplace in the Global South. Out of sight, out of mind.

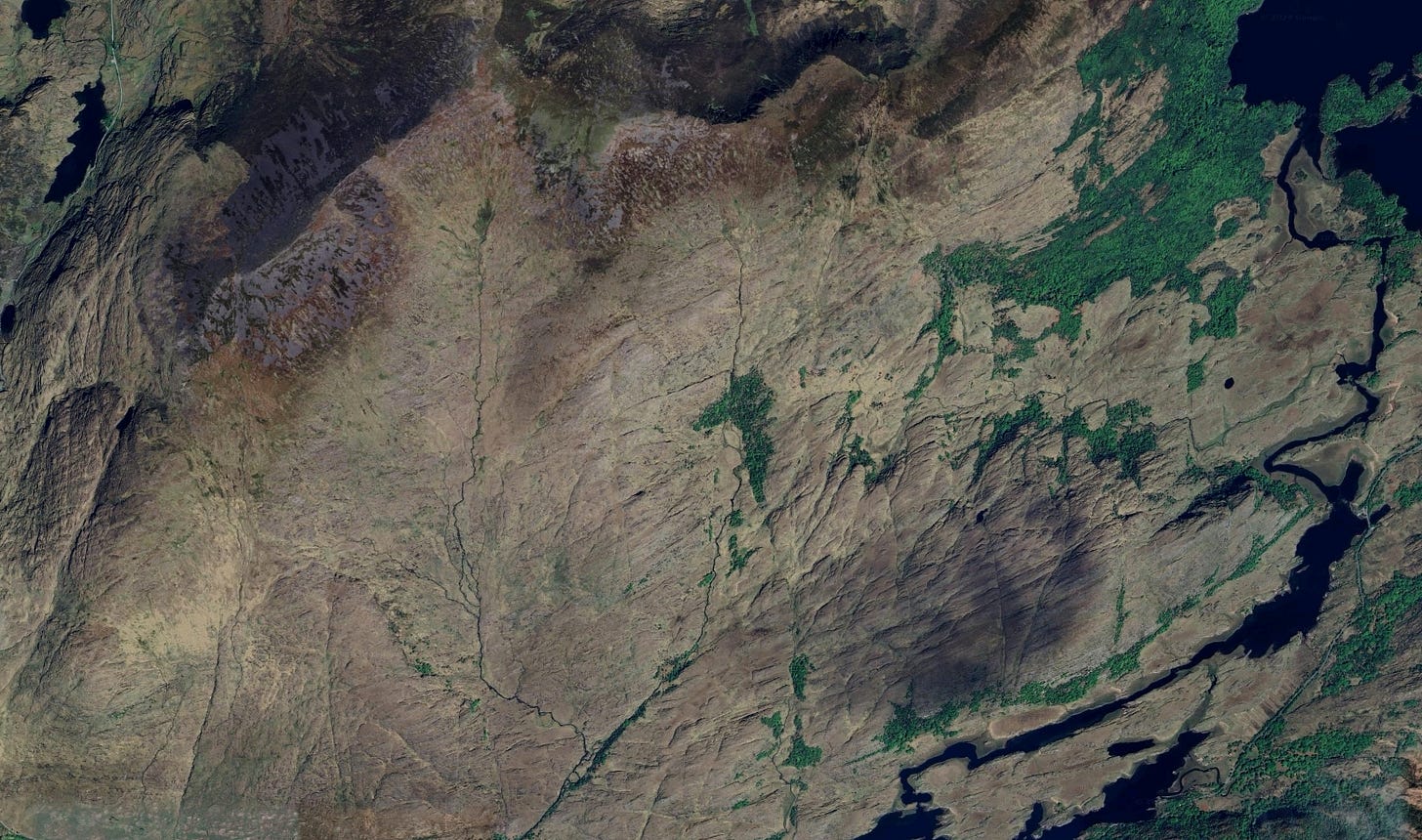

What about these grey-brown areas mostly on the edges of the island?

These are Ireland’s mountains — bare and ecologically devastated places that once would have had vibrant, sprawling forests and all kinds of inhabitants. Nowadays you’ll mostly find some heather, some bilberry bushes that don’t seem to fruit very often anymore, the odd skylark, sheep, ravens cleaning up dead sheep, and large deer herds. They are also interspersed with commercial timber plantations.

Roads

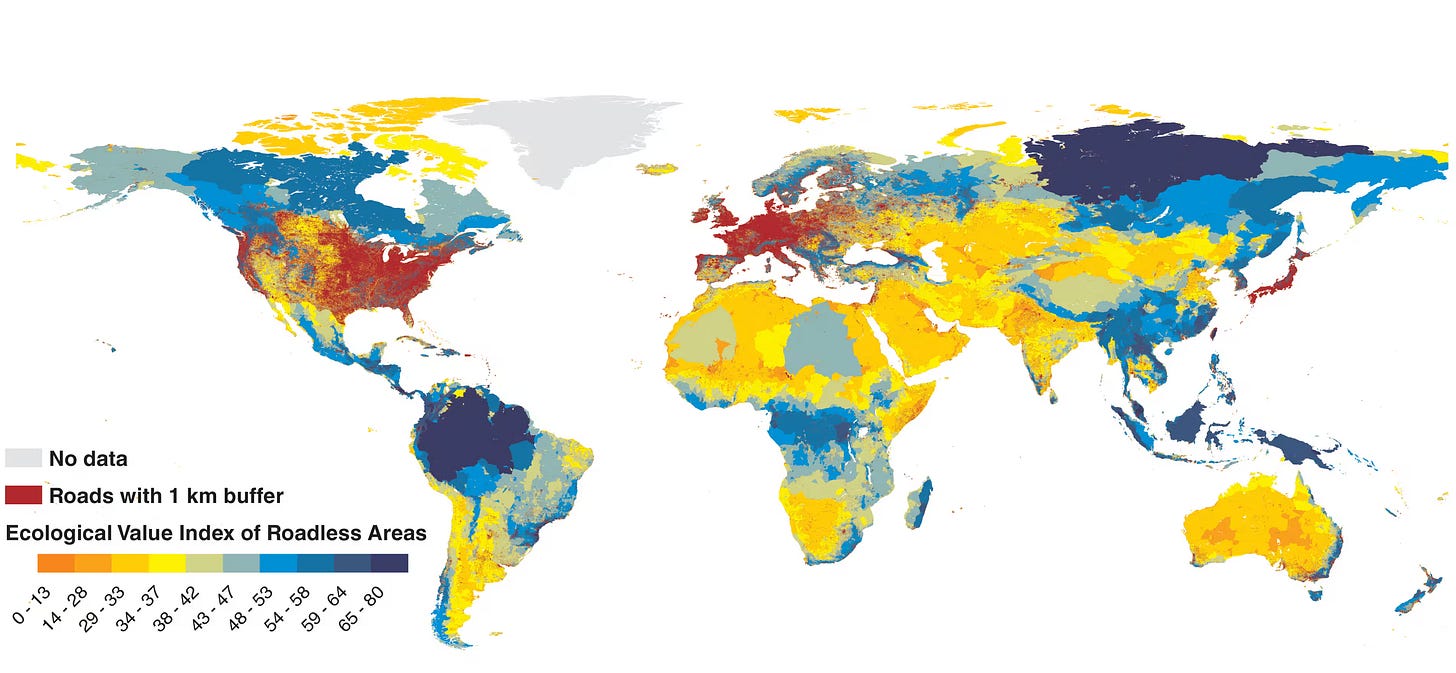

This map below depicts how roads adversely affect “wildlife”. I put “wildlife” in scare quotes because I find the word a bit ridiculous. How we conceptualise these things matters for how we view ourselves and our place on the land in relation with the rest of life. “Wildlife” constitutes ALL other animal beings on the land except for domesticated ones that we either keep as pets and companions or directly control in some way. It does however point to a core predicament, that life has been divided into ‘wild’ and ‘domesticated’. On the matter of roads, Ibisch et. al. (2016) in this article write,

“The impact of roads on the surrounding landscape extends far beyond the roads themselves. Direct and indirect environmental impacts include deforestation and fragmentation, chemical pollution, noise disturbance, increased wildlife mortality due to car collisions, changes in population gene flow, and facilitation of biological invasions (1–4). In addition, roads facilitate “contagious development,” in that they provide access to previously remote areas, thus opening them up for more roads, land-use changes, associated resource extraction, and human-caused disturbances of biodiversity (3, 4).”

We can see here that Ireland is completely red on this projection, in other words the entire island is adversely affected by the existence of roads. Anyone who lives here or has been here can easily attest that it’s almost impossible to find somewhere to be “in nature” where you can’t hear road noise or some other noise related to the activities of industrial society. This research additionally makes it somewhat comical to consider that the ‘Wild Atlantic Way’ on Ireland’s west coast follows busy national roads for most of its 2,600km length. Not really so ‘wild’, but tourism marketing is based on the commodification of romanticised fantasies unmoored from the realities of the land and human communities in whatever place is being sold for consumption.

Even some of these images of roads look visually green. It should go without saying that the dominance of the colour green itself does not imply ecological intactness in any way. Golf courses even look green:

Or when we obsess about ‘green spaces’ in our cities, what does that really mean? Who is it for? Those tiny, compartmentalised ‘green spaces’ are often more for humans (and not even all humans at that) than for anyone or anything else. They can certainly never become a thriving ecosystem. They can never become places of ecological dignity or autonomy:

‘Renewables’

It is beyond farcical that wind turbines and solar panels have become known as ‘green energy’, when these destructive industrial technologies are not only a continuation of the modern/colonial extractivist paradigm, but necessitate a scaling up and intensification of it. Not only do they create sacrifice zones on our own land where enormous areas are being filled with them, but they necessitate ecocide elsewhere to produce the materials necessary for their construction and continual maintenance. Alexander Dunlap has suggested instead using the term ‘fossil fuel+’. I have written a bit about so-called ‘renewables’ here:

Some other instances of ecocide

This image showing the shores of Lough Neagh looks very green. The green in the water is in fact cyanobacteria (aka blue-green algae) that is suffocating the lake’s ecosystems. It is nothing short of a cataclysm for the lake and its inhabitants:

This image is of Aughinish Alumina on the Shannon River in Co. Limerick. It is a bauxite refinery that produces alumina used in the manufacturing of aluminium. People in the locality have reported instances of rare cancers and their livestock falling ill and dying.

Then we have a commercial quarry, of which there are hundreds in Ireland. This one is next to a golf course, and there happens to be an ancient cairn of some description wedged in between them (not visible in the image):

Ardnacrusha power station was constructed in 1929. It provided a sizeable portion of Ireland’s electricity for many decades and is still in operation. The dam which sits in Ireland’s largest river — the Shannon — has caused a reduction of over 90% in salmon populations.

Ecological intactness

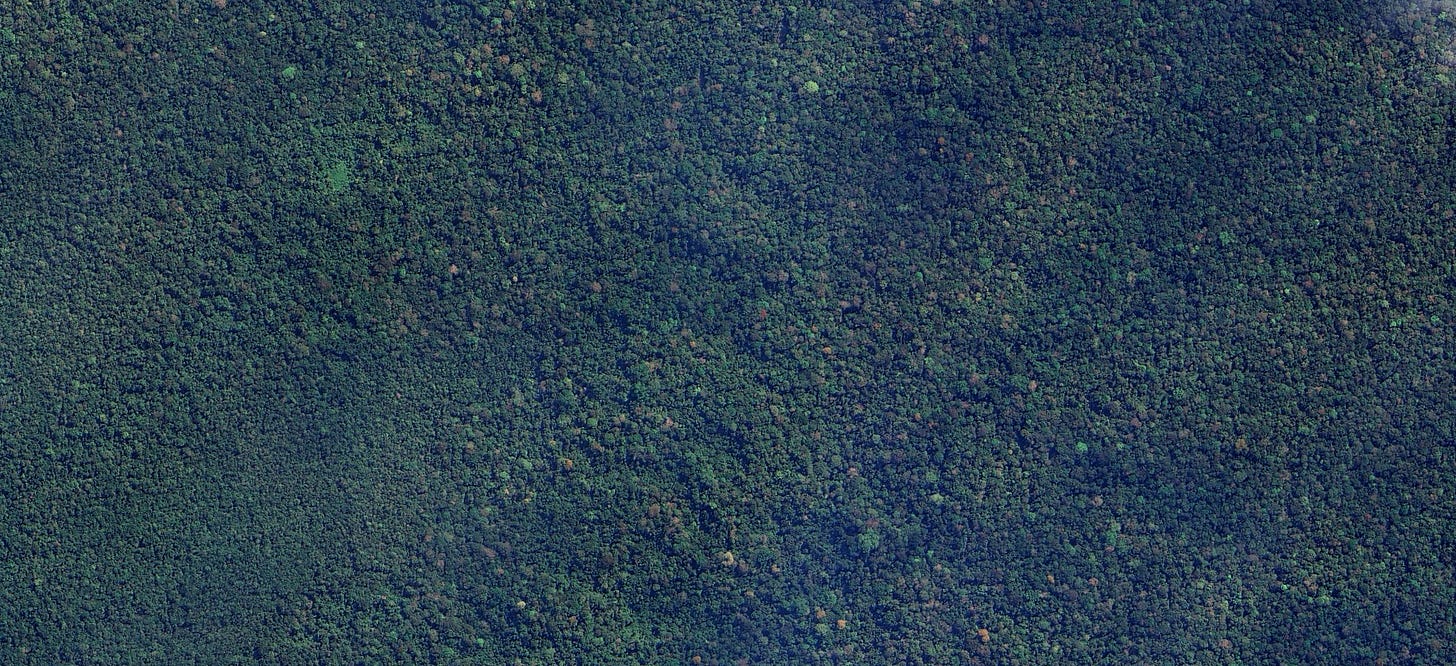

Whereas, in the Amazon for instance, it’s still easy to grab screenshots of dense forested landscapes like this that can stretch for hundreds of kilometers around:

Or in Siberia:

These are ‘green’ landscapes in both its literal and metaphorical sense — or as close as any place can get to it nowadays because everywhere is affected or threatened in some way by modern civilisation. Nothing short of autonomy for the land and all the beings within can truly qualify as ‘green’, ie. ‘environmentally friendly’ or ‘ecologically intact’. We’re fooling ourselves to imagine that enclosing tiny enclaves for conservation, be they national parks or meagre ‘green spaces’ or a single field, marks any kind of justice or acceptable compromise for the severe damage modern civilisation is doing to the Earth, let alone that it’s any kind of move in the ‘right direction’. The ‘right direction’ begins the moment we take what is happening seriously enough to ask how we can move away from the inherent violence of modern/colonial civilisation, and start moving towards ecological autonomy in our different contexts — a dignified, re-integrated life without states, without patriarchy, without extractivist economies; worlds rebuilt on care for humans, the land, and all beings. I say ‘rebuilt’ because such worlds have been and are continuously being annihilated and suppressed by modern/colonial civilisation. Our callous, violent world did not come about by accident. I plan to write more about these ideas in the coming months, so consider subscribing if you want updates.

So long as we continue to inhabit and reproduce modern lifeways, we can delude ourselves all we want with a long, sorry, growing list of non-solutions, avoidance strategies, or PR strategies fed to us by large corporations such as: recycling, conservation, carbon footprints, carbon credits, ‘renewable’ energy, ‘ethical’ consumerism, electric cars, voting ‘green’ (or imagining we can vote away our predicaments in any direction), ‘alternative’ economies (Doughnut economics, Wellbeing economy etc), SDGs, biking to work, sustainablah, blah, blah.

Some of these things may be well intentioned (and some were always about manipulation), but at the risk of being cliché: the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Good intentions aren’t taking our predicaments seriously enough.

Well that’s lovely! Are we supposed to just be miserable about this now?

While grieving is needed, becoming enclosed in pain is not. The land’s ever-shifting baseline has us confused about what ‘natural’ and ‘wild’ landscapes look like in Ireland. We are in a profound state of cultural amnesia — Ireland is a truly ecologically devastated place, and the normalisation of that is written into our culture. I don’t insist on this point throughout what I write because I want us to sink into immobilised misery about this fact, I insist because I want us to face the devastation so that we can set about taking necessary actions. We need to defend the land from the ecocidal actions of the state and capital, to set about healing our relationships with the land, and most of all to set about healing our relationships with each other. Much easier said than done. The wounds are deep and getting deeper. I believe facing the severity and true depths of our predicaments is the first step to being able to take such action that isn’t doomed to recreate the same issues or even worsen things.

This St. Patrick’s day, as thousands of people binge green-hued alcoholic beverages to dull the pain of living in an ecologically disintegrated world, consider that Ireland is not at as ‘green’ as is so commonly portrayed in mainstream media, corporate propaganda, or tourism marketing.

And that it doesn’t have to be this way.

Ecocide is an iterative process, and that process is socially reproduced. It can also be socially interrupted.

Check out my Decolonization in Ireland online course

All satellite image credit: Google.

Such a solid land survey. Thank you! 👏

Fabulous essay. Excellent points and the maps really bring your points to life. I have been writing on the same lines myself on my own Substack.

There is also the cultural damage, as well as the loss of language our heritage has also been commodified and repackaged.

Have you read Eoghan Daltons book about the Irish Atlantic Rainforest?